In centuries past, villages such as Eastington were no strangers to outbreaks of often fatal diseases -

Regular readers might recognise the name Henry Hicks. He’s cropped up in a number of earlier articles, having been Eastington’s Lord of the

Manor, and owner of land, property and mills. Latterly, it was Hicks and his family that was largely responsible for developing much of the local woollen cloth making industry, at one time carried out in five local mills in and around the village.

Having been requested by my friend, Mr. Henry Hicks, of Eastington, in this county, to inoculate two of his children, and at the same time some of his servants and the people employed in his manufactory, matter was taken from the arm of this boy for the purpose. The numbers inoculated were eighteen. They all took the infection, and either on the fifth or sixth day a vesicle was perceptible on the punctured part. Some of them began to feel a little unwell on the eighth day, but the greater number on the ninth. Their illness, as in the former cases described, was of short duration, and not sufficient to interrupt, but at very short intervals, the children from their amusements, or the servants and manufacturers from following their ordinary business.

Three of the children whose employment in the manufactory was in some degree laborious had an inflammation on their arms beyond the common boundary about the eleventh or twelfth day, when the feverish symptoms, which before were nearly gone off, again returned, accompanied with increase of axillary tumour. In these cases (clearly perceiving that the symptoms were governed by the state of the arms) I applied on the inoculated pustules, and renewed the application three or four times within an hour, a pledget of lint, previously soaked in aqua lythargyri acetati (a solution of lead diacetate, apparently!), and covered the hot efflorescence surrounding them with cloths dipped in cold water. The next day I found this simple mode of treatment had succeeded perfectly.

So it seems that all the guinea pigs came through the treatment safely!

The development of Hicks’ woollen cloth business brought him into contact with a number of influential colleagues and contacts in the industrial world, some of whom were major players on the national stage. However, his sphere of contacts extended well beyond this, and he also had a number of important social connections. One of the most notable was Berkeley resident Dr Edward Jenner of smallpox fame. As everyone knows, Jenner was the country doctor who championed vaccination, having discovered in 1796 that inoculation with cowpox provided immunity to smallpox.

An epidemic of smallpox had swept through Gloucestershire in 1788 and Jenner was one of the doctors involved in treating the outbreak. He noticed that people previously infected with the much milder cowpox escaped the ravages of smallpox and noted that even when entire families succumbed to smallpox, cowpox victims remained unaffected and healthy. In 1796 Jenner carried out his first inoculation experiment and within a short period, it became apparent how effective the vaccination treatment was.

Jenner and Henry Hicks were close friends. In their frequent correspondence, Jenner usually affectionately addressed the latter as ‘Harry’. Alongside his medical activities, Jenner was also a keen naturalist. For example, in 1788, a publication called Philosophical Transactions contained a long paper of his that examined the behaviour of the Cuckoo. For some reason, it was apparently written in a cottage that was owned by Henry Hicks and stood close to his home in Eastington.

Hicks was clearly confident enough in Jenner’s vaccination work to let him loose on two of his own children, along with 16 servants and workers from Churchend Mill (I wonder how enthusiastic they actually were!).

The inoculations took place in Eastington on 27th November 1798 using cowpox ‘matter’ obtained from the arm of a farm boy in Stonehouse the day before.

Later the same year, Jenner wrote:

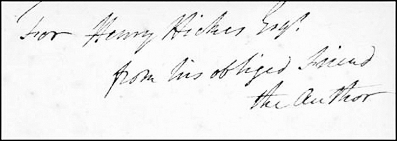

Jenner’s personal dedication to Henry Hicks signed inside the cover of one of his books, the snappily titled ‘An Inquiry into the Causes and

Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease

Discovered in some of the Western Counties’.

It reads for “Henry Hicks Esq, from his obliged friend. The Author“.

Stephen Mills

Amongst his other achievements, Jenner was instrumental in forming a society of learned men aimed at improving medical science. Meetings were held mainly at the Fleece Inn, Rodborough where, after serious discussions, members dined together. They occasionally permitted visitors, who were not medical men, to join them for dinner. Hicks (Jenner’s “faithful friend”) was often picked up in Eastington by Jenner on his way from Berkeley and taken in his carriage to the meetings. He was the most frequent non-

In 1823, Jenner died after an 'apoplectic seizure with paralysis of the right side' (a stroke). Fittingly, Hicks was with him at the end. Hicks himself died in 1836.

In 1853, smallpox vaccination was finally made compulsory in England and Wales. It’s nice to think that Eastington was part of the early story of inoculation and played

albeit a small role in a process that has since saved millions of lives around the world.

An early painting of Eastington Park, the Hicks’ family home. It was built by Henry Hicks in 1815.

This is how Edward Jenner, a regular visitor, would have known it.

After these experiments were concluded, Hicks was widely credited as the “the first gentleman that submitted his own children to the new practice”. This gave some confidence to the gentry, and his example was soon followed by the Countess of Berkeley and Lady Francis Moreton (later Lady Ducie). Indeed, it’s recorded in the British & Foreign Medical Review of July-

Dr Jenner and Henry Hicks